An article I read on HackerNews recently talks about video games as a new direction in learning. It touches on some points that I also believe in – a lot of what stuck with me from my childhood was from learning on my own, and not as much what was taught directly.

In elementary school, I was a huge Pokemon fan, and I basically memorized every Pokemon in the first 4 generations. No one taught me this through tests or anything, it was just a natural consequence of the game world. I had to learn things like strategizing, type advantages, and game-theory-ish tactics. In middle school and even until today, I played a lot of Minecraft. There’s no explicit goal in Minecraft, but the implicit one is always to build up a great base and gear up. Since I played with friends, there was always this aspect of command structure – someone had to form the plans and lead everyone down the right path.

A book I read recently, “The Coddling of the American Mind”, stresses the importance of free play in childhood development. Children which are allowed to run free on the streets develop a sense of self-independence. In free play, kids learn to judge risk and push their limits. First you build up confidence in running, then you try to handle the swings, then you can try to jump off the swings and land on your feet. There was never any explicit curriculum, but the playground is an environment that naturally encourages to judge on their own what they are capable of. Free play takes place when the environment encourages setting your own goals, and trying your best to figure out how to achieve them.

A concern in “The Coddling of the American Mind” is that free play given to kids has fallen dramatically in recent years, due to safety concerns and/or busy schedules of lessons. I find it interesting that in my experience, the free play that I learned the most from came from unsupervised time online. Games were some of this, but the greatest game of all was the stuff surrounding them.

To break the password and time limits my parents put on our computer, I had to learn how the BIOS worked. I had to learn basic networking to set up a Minecraft server for my friend group. At some point, I wanted a domain name, but I didn’t have a credit card, so I had a month-long venture into shady Paypal tactics and eBay scams to earn a few dollars.

There are some games that push the “free play” paradigm very well, and they are usually the ones without a structured goal. Minecraft has no end game, and it’s all about setting goals for yourself and accomplishing them. Titles like Factorio and Stardew Valley have an open-ended end goal (earn a lot of money), but let the player figure out how to break down and achieve it on their own.

The current interpretation of “educational games” is usually something like Dora Teaches Math, aimed at teaching facts through a gameplay loop. But a huge potential in educational games is building up the fundamental goal-setting and planning ability of kids through these open-ended, free play environments. Throw in a few friends, and it’s endless entertainment that actually produces worthwhile experience.

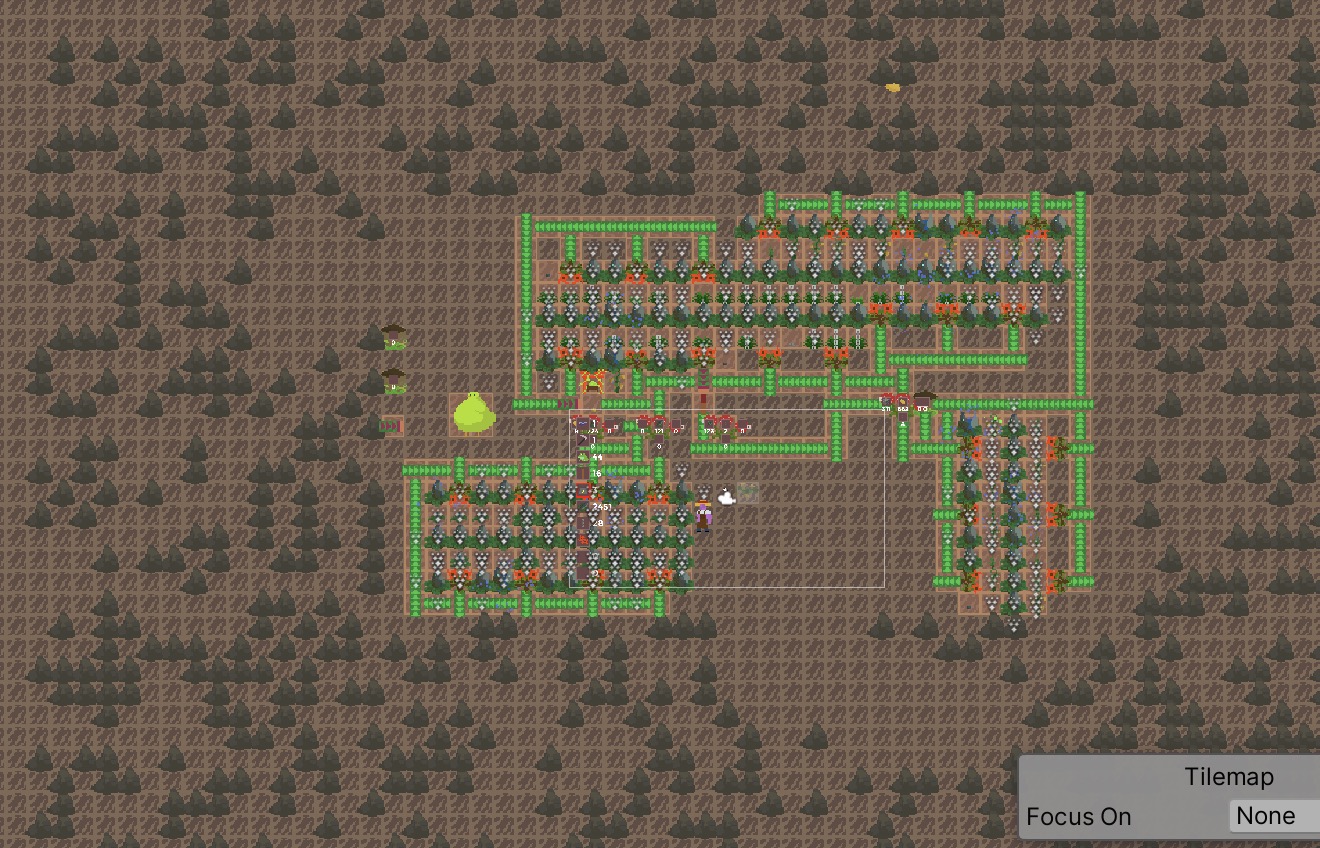

Stardude Alley is the first week-long game from Kirisame Jump. As a farmer who inherits a farm loaded with debt, you are tasked with rebuilding the land to its former glory. At first, growing plants takes manual labor such as watering and harvesting, but as you progress, you can build structures such as auto-watering plants, auto-harvesters, pipes and crafters.

In Stardude Alley, our main goal was to build an engaging game loop around long-term planning. While the core systems are simple, the player has freedom to make plans as complex as they want to, from “automate plant watering” to “build a production line for bombs”.

Prev Post || Next Post